Biography

Sabú era simplemente Jorge Ruiz , un niño de Buenos Aires que dormía en parques y robaba fruta para alimentar a su hermana pequeña tras la muerte de su madre. Su gran oportunidad llegó por accidente. Llenó teatros por toda Latinoamérica y cantó en seis idiomas, pero murió en silencio, con una camiseta que decía “Colombia te ama”.

Lo invitaron a cantar en un desfile de moda, lo descubrieron dos productores y de repente se encontró en el centro de la fama.

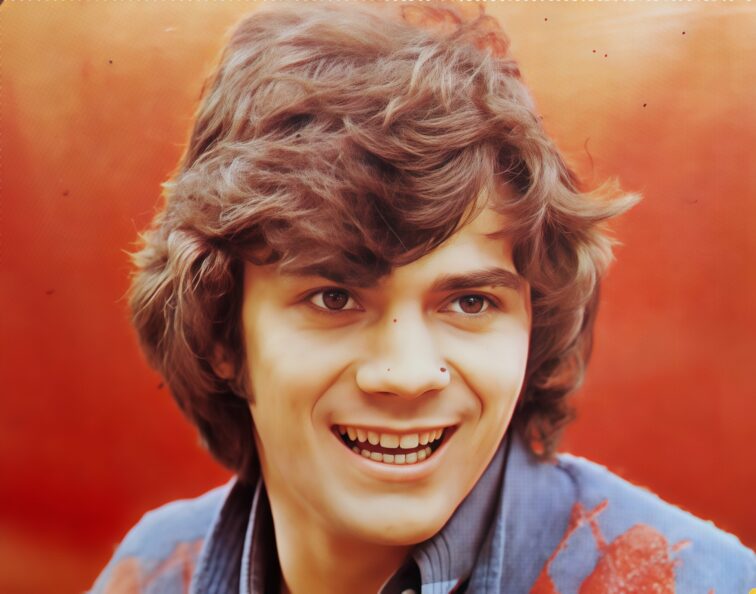

¿Cómo se convirtió este niño fugitivo en un ídolo del pop latino? ¿Y por qué terminó todo tan trágicamente? Esta es la verdadera historia de Sabú, de niño de la calle a superestrella. Héctor Jorge Ruiz Saccomano nació el 12 de septiembre de 1951 en las densas calles obreras de Monserrat, uno de los barrios más antiguos de Buenos Aires. Entre iglesias coloniales y fachadas desmoronadas, Monserrat era un lugar cargado de historia, pero también de pobreza.

Allí, Jorge dio sus primeros pasos en un mundo que lo daría todo, pero también se lo quitaría todo. Era el primogénito de Héctor Ruiz, un hombre severo y distante, y Susana Elsa Saccomano, una madre cálida pero frágil que se convirtió en el centro de su universo. Hasta que la perdió.

Cuando Jorge tenía apenas seis años, su madre falleció. Las circunstancias nunca se comentaron a fondo, ni siquiera en familia, pero su ausencia destrozó su pequeño hogar. Sin ella, todo se vino abajo.

Su padre se volvió a casar unos años después, con una mujer que le dejó claro que los hijos de su nuevo marido no eran bienvenidos. A los nueve años, Jorge y su hermana Silvia, de solo seis, se quedaron prácticamente sin hogar. Empezaron a pasar más tiempo en la calle que en casa. Luego fueron días enteros. Y luego, noches enteras. Lo que empezó como una forma de escapar se convirtió en una lucha por la supervivencia. Y sobrevivir en las calles de Buenos Aires en la década de 1960 era todo menos romántico. Era violento, desesperado y, a menudo, anárquico. Dormía en parques.

Se escondía bajo los puentes. Compartía pan duro con otros niños sin hogar y robaba fruta de los puestos cuando el hambre se volvía insoportable. Años después, recordaría a un vendedor del que sospechaba. Lo vio robar, pero nunca lo detuvo. «Creo que me dejó», decía. Vio que yo era solo un niño.

La calle se convirtió en su escuela. Y en esa escuela, encontró a tres amigos que cambiarían su vida: Juan Carlos, Luisito y Eduardo. Todos eran huérfanos de hecho, aunque no de nombre. Juntos mendigaban, robaban y se cuidaban como hermanos. Jorge los llamaba sus “hermanos del corazón”.

«Muchos de mis amigos de aquella época acabaron en la cárcel», confesó una vez. «Yo no, quizá porque siempre creí que algo mejor era posible». Y perseguía ese «algo mejor» con un ansia más profunda que la de su estómago.

Su primera vía de escape fueron los deportes. Era rápido, ágil y competitivo. Se presentó a las pruebas para las categorías inferiores de Boca Juniors, el club más grande de Argentina , y fue aceptado. Era una oportunidad que pocos niños de su comunidad tenían, pero mientras otros tenían botines y uniformes pagados por sus padres, Jorge tuvo que elegir entre entrenar o trabajar para comer. Nadie en casa lo apoyaba. No podía permitirse soñar.

Así que renunció. Para sobrevivir, aceptó cualquier trabajo que encontró. Repartió periódicos al amanecer, lustraba zapatos en cafés del centro y trabajaba en turnos de noche en edificios, durmiendo a escondidas en sótanos. Hasta que un golpe de suerte cambió su destino. Alguien le dijo que la casa de moda Modart buscaba jóvenes para su nueva línea de ropa. Jorge llegó sin experiencia, pero su mirada intensa, mandíbula pronunciada y porte natural los impresionaron.

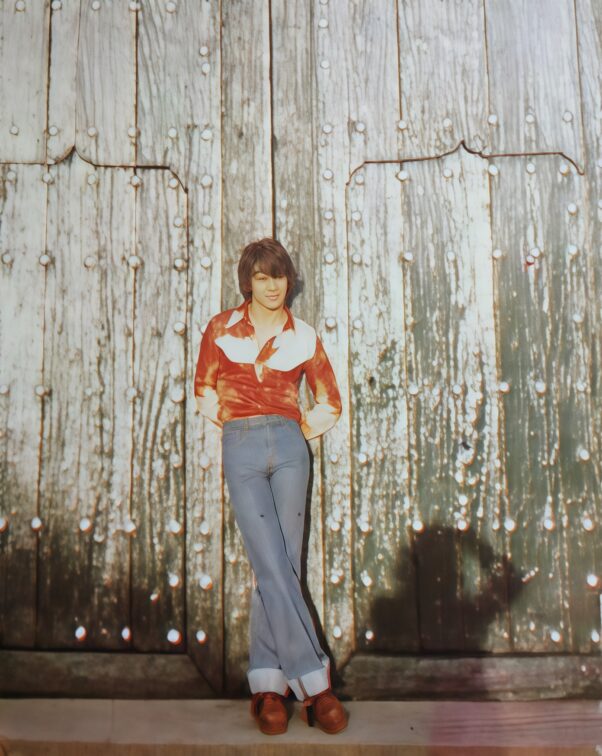

Lo contrataron al instante. Bajo el alias de Giorgio, empezó a trabajar como modelo. Desfiles de moda, sesiones de fotos, revistas. De repente, las luces reemplazaron a las farolas. Pero aunque las cámaras lo adoraban, él sabía que no era su verdadera vocación. Algo le faltaba.

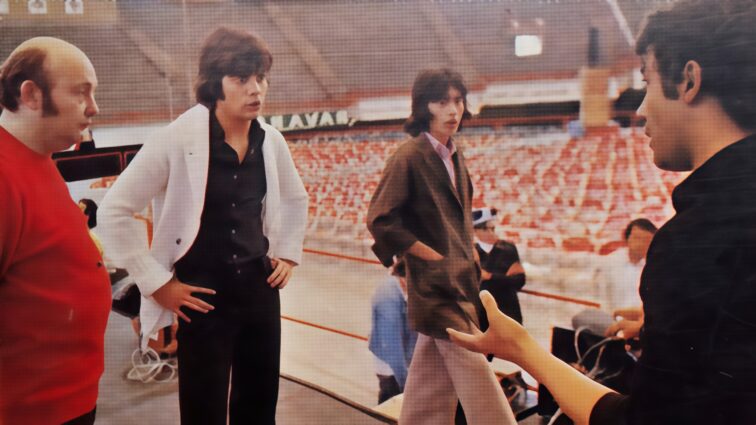

Y ese algo apareció por casualidad una noche de 1968. Después de un desfile de moda, los organizadores, medio en broma, le pidieron que cantara algo para entretener al público. Sin pensarlo, tomó el micrófono y comenzó a cantar. Su voz, ronca, profunda y melancólica, acalló el murmullo de la sala. El destino quiso que dos importantes productores, Ricardo Kleiman y su socio, estuvieran entre el público buscando nuevos talentos. No solo oyeron una buena voz; vieron una historia, una estrella, un superviviente.

Kleiman se acercó a él después del evento. “¿Tu nombre?”, preguntó. “Giorgio”, respondió Jorge. “No”, dijo Kleiman sonriendo, “es el nombre de un maniquí. ¿Cuál es tu verdadero nombre?”. Jorge dudó. Luego, casi con timidez, mencionó el apodo que le habían puesto sus amigos de la calle, Sabu, en honor al actor indio de El ladrón de Bagdad, un joven pícaro que venció al mal con astucia y valentía.

Kleiman asintió. «Perfecto», dijo, «será Sabú». Y así, de aquel chico que una vez robaba pan para sobrevivir, nació una estrella. Nació Sabú. A los productores les encantó lo que oyeron. Pero Giorgio no funcionaba como nombre artístico.

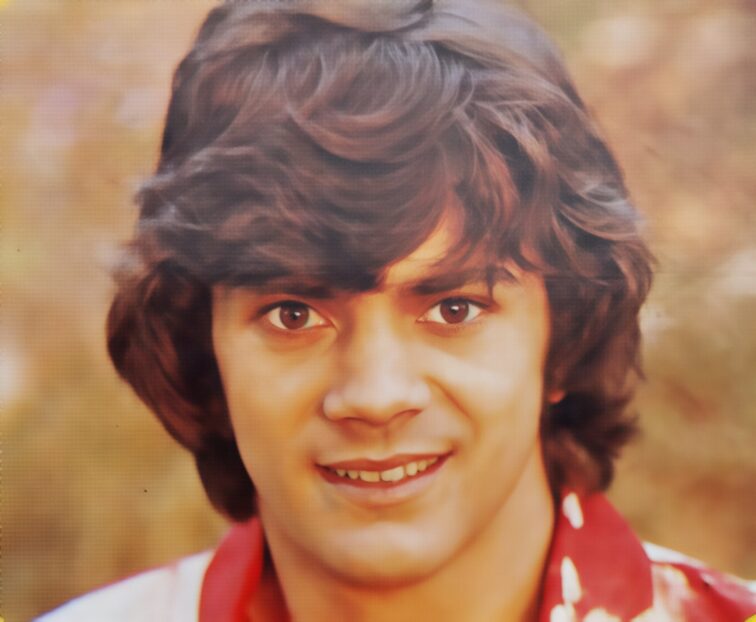

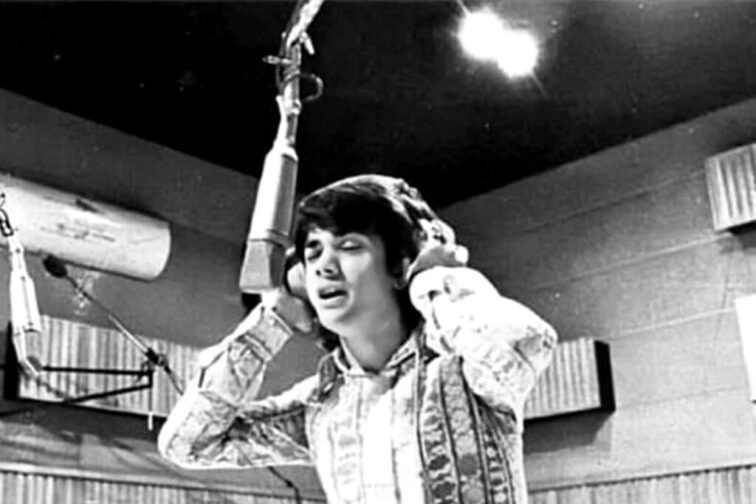

Luego les contó sobre su apodo de la infancia, Sabú, en honor al actor indio famoso por El ladrón de Bagdad. “Tuvimos infancias parecidas”, explicó. “Inicios difíciles, pero grandes sueños”. Y así nació Sabú. En 1969, con tan solo 18 años, lanzó su primer sencillo, “Toda mía la ciudad”. La canción fue un fenómeno, vendiendo más de 50.000 copias, cinco veces más de lo que cualquier artista nuevo podría desear.

Su siguiente canción, “Ese tierno sentimiento”, superó incluso ese éxito. Pero Sabú no era un ídolo adolescente más fabricado por una disquera. Él mismo hacía las llamadas, negociaba apariciones y usó todo su instinto de supervivencia para forjar su nombre.

En poco tiempo, cantaba por toda Latinoamérica. Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Perú y Puerto Rico lo recibieron con estadios llenos. Para 1971, cada uno de sus discos vendía más de 100,000 copias, y su voz se escuchaba en seis idiomas.

Ese mismo año, viajó a Francia para grabar en francés y luego a Londres para una gira promocional. Cantó en el icónico programa de variedades español ” Sábados Gigantes “, apareció en la televisión brasileña junto a Roberto Carlos e incluso viajó a Tokio, donde compartió escenario con Quincy Jones y John Lennon. A sus 20 años, vivía un sueño que nadie hubiera imaginado posible para aquel chico que una vez robó manzanas en las calles de Buenos Aires. Estrenó dos películas, grabó nuevas canciones y realizó giras internacionales.

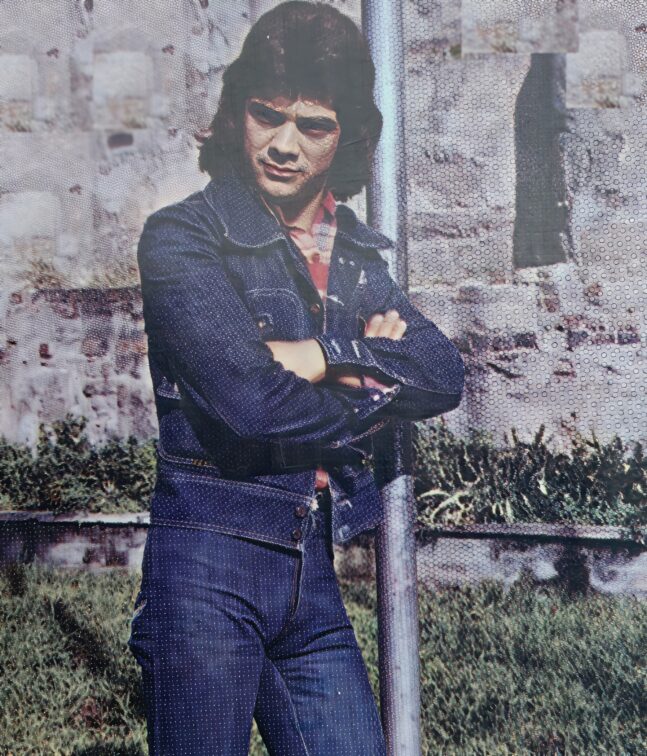

En 1978, Sabú desapareció. Empacó sus maletas y se fue. No solo a Buenos Aires , sino al continente. Primero a Nueva York , donde intentó perderse en el caos de la ciudad. Luego a Puerto Rico , donde aún brillaba con fuerza. Pero el lugar que realmente le ofreció una segunda oportunidad, un refugio y un futuro fue México .

Allí, lejos de los buitres del escándalo argentino, Sabú comenzó a reconstruirse. No solo su carrera, sino su vida. A principios de los 80, el largo camino de reinvención de Sabú encontró un nuevo capítulo en México.

Tras años de silencio y algunas giras esporádicas, firmó un contrato exclusivo con Melody Records, el sello musical de Televisa , el imperio mediático más poderoso del mundo hispano. No fue solo un contrato discográfico. Fue un salvavidas. Una segunda oportunidad. Un país listo para acogerlo como la voz eterna de la balada romántica latinoamericana. Y Sabú no la desperdició.

Entró al mercado mexicano con el anhelo de quien ha conocido la pérdida y con una voz impregnada de toda esa experiencia. Grabó una serie de sencillos que arrasaron en la radio, incluyendo “Quizás sí, Quizás no” y “Fiebre de ti”. Ambas canciones se convirtieron en éxitos masivos en México y Centroamérica , apareciendo en recopilatorios románticos, programas de variedades y telenovelas de Televisa .

Pero Sabú no se conformó con simplemente revivir su propia carrera. Vio algo roto en la industria musical latina: artistas jóvenes sin guía, sin protección ante la despiadada maquinaria de la fama. Así que decidió construir algo diferente.

Fundó su propia productora, Sabú Producciones , y comenzó a trabajar como mentor y productor de nuevos talentos. Su colaboración más famosa fue con Lupita D’Alessio, una de las voces más poderosas y temperamentales de México. Cuando se conocieron, Lupita estaba en ascenso, pero emocionalmente perdida, impulsiva, frágil y atormentada por sus demonios internos.

Se convirtieron en amantes. La conexión fue electrizante. Dos artistas atormentados, ambos marcados, ambos en busca del control, capaces tanto de la genialidad como del desastre. Juntos crearon música que parecía arrancada de las páginas de su propia historia de amor. Apasionada, caótica, inolvidable. Pero al igual que las canciones que compusieron, su historia tuvo un final dramático.

La intensidad que alimentaba su arte se volvió tóxica en la vida real. Las discusiones se intensificaron. La confianza se rompió. Sus extremos emocionales chocaron irreconciliablemente. Y cuando terminó, terminó para siempre, tanto profesional como personalmente. Sabú nunca habló públicamente de la ruptura, pero con el tiempo, sus amigos se dieron cuenta de que nunca volvió a trabajar tan de cerca con nadie.

Poco después, a mediados de los 80, Sabú conoció a alguien que cambiaría su vida. No con pasión, sino con serenidad. Josefina Gil , cantante argentina residente en México, había formado parte del famoso grupo Las Hermanas Gil, junto con sus hermanas Noemí y Gloria .

Poco después, a mediados de los 80, Sabú conoció a alguien que cambiaría su vida. No con pasión, sino con serenidad. Josefina Gil, cantante argentina residente en México, había formado parte del famoso grupo Las Hermanas Gil , junto con sus hermanas Noemí y Gloria.

A diferencia de Lupita , Josefina no perseguía titulares ni escándalos. Había dejado atrás la fama y vivía una vida tranquila en México, criando a su hija Faye, quien años después también se convertiría en estrella del pop. Sabú se sintió atraído por la serenidad de Josefina, su elegancia y su profunda comprensión de la música y el dolor. Su relación no fue una explosión instantánea, sino una lenta recuperación. En noviembre de 1987, se casaron en una ceremonia íntima, lejos de los paparazzi. Josefina le dio algo que él nunca había tenido: paz.

Pasaron los siguientes 18 años juntos, compañeros en el amor, la música y la supervivencia. Pero no sin heridas. Sabú nunca tuvo hijos. Su relación con Fey era distante. Cuando la adolescente cumplió 15 años, decidió vivir con su tía Noemí en lugar de mudarse con su madre y Sabú . Aunque mantuvieron un contacto cordial, el vínculo nunca fue profundo.

Y quizás más doloroso que eso fue el distanciamiento de su propia hermana, Silvia , la chica a la que una vez protegió en las calles de Buenos Aires. Pasaron los años, luego las décadas. Se veían ocasionalmente, pero cada encuentro era más frío. Algunos decían que la distancia era emocional, otros que el pasado pesaba demasiado como para reabrir viejas heridas. Así que Sabú se volcó por completo en lo único que nunca lo había traicionado: la música.

Durante los 80 y 90, produjo álbumes para otros artistas, ofreció conciertos selectos y continuó asesorando a nuevos talentos. Su hogar en México se convirtió en un pequeño y tranquilo centro creativo, pero constante. Por fin, dejó de huir. Por primera vez, pertenecía a algún lugar. Y a alguien. Y entonces, tras años alejado de los focos, regresó.

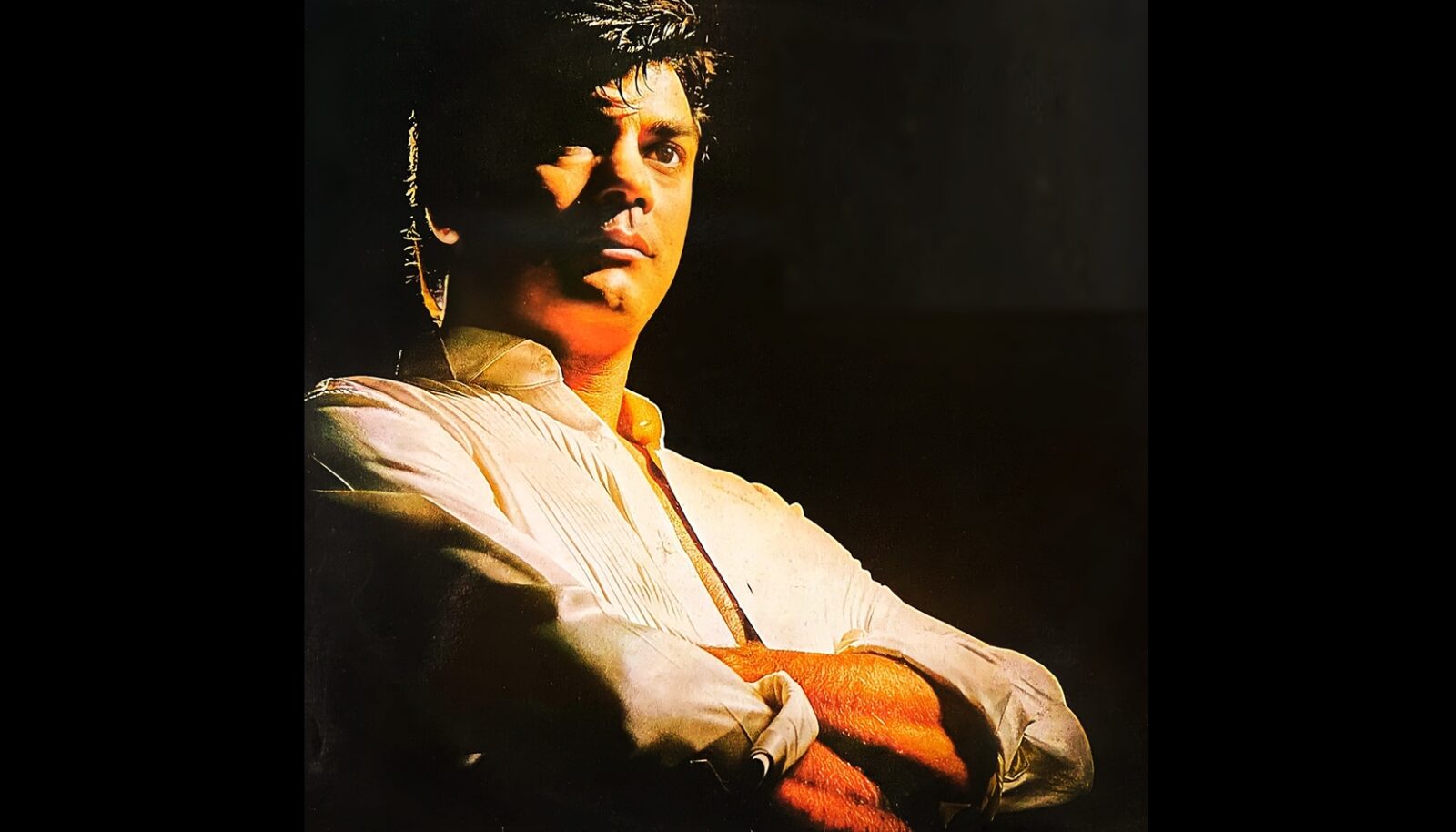

Para 1991, Sabú llevaba casi una década fuera del radar. Los escándalos de los 70, su salida de Argentina, su retiro parcial de la fama. Muchos creyeron que había desaparecido. Pero en realidad, Sabú estaba esperando. Esperaba la canción perfecta. El momento perfecto.

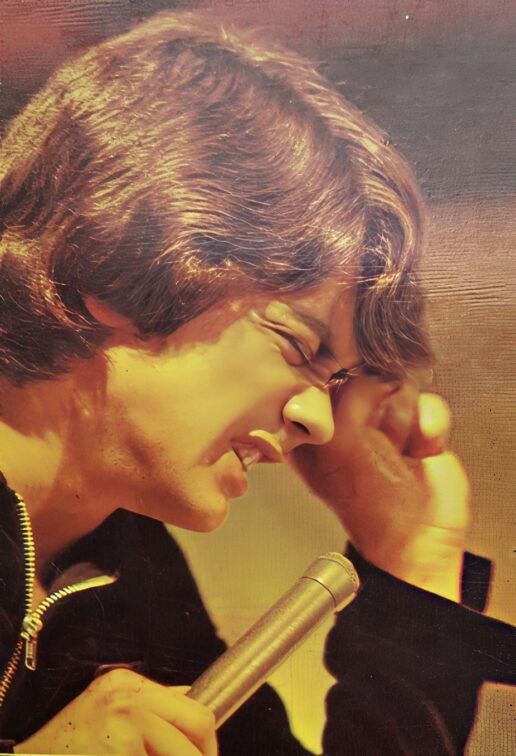

El país indicado. Ese momento llegó en Colombia. Invitado al prestigioso FestiBuga , el festival de música más importante del Valle del Cauca, Sabú regresó al escenario ante un público masivo que nunca lo había olvidado. Inauguró el concierto con un nuevo sencillo, “¿Con quién vas a pasar esta noche?”. Y en cuestión de segundos, la multitud estalló. No era simple nostalgia.

Fue una resurrección. La voz seguía ahí. Más profunda. Más rica. Marcada por las cicatrices y la fuerza de los años. Su carisma no había envejecido ni un solo día.

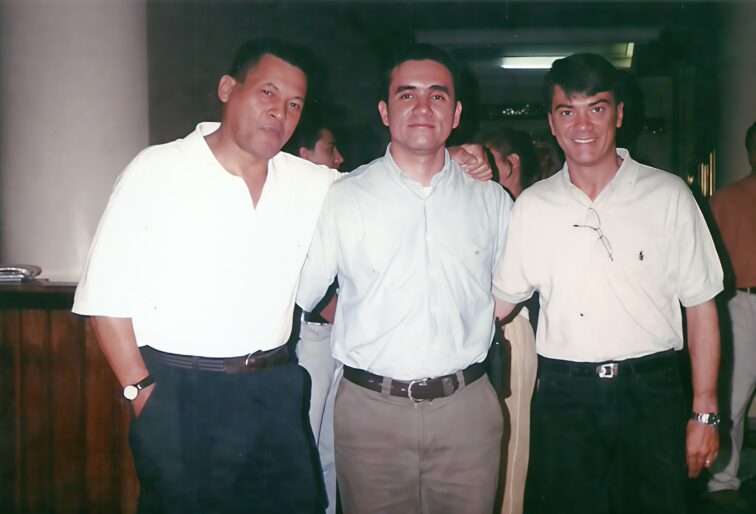

Al contrario, se había vuelto más sereno, más magnético. Ya no era el ídolo adolescente de los 60. Era una leyenda que regresaba del exilio. El éxito en Colombia reavivó su carrera. Sabú se embarcó en una gira a gran escala por Latinoamérica. Encabezó conciertos en Puerto Rico , Venezuela , Ecuador y México .

En Estados Unidos , actuó en los principales escenarios latinos de Miami, Nueva York y Los Ángeles, reconectando con una generación que creció escuchando sus discos. Pero fue Colombia la que le dio más que solo aplausos. Le dio un hogar.

Sabú incluso llamó al país “mi segunda patria”. Sus fans lo recibieron no como una estrella caída, sino como un superviviente, un guerrero de las canciones de amor. Se convirtió en un invitado frecuente de la televisión colombiana, grabó en Medellín e incluso consideró mudarse allí definitivamente.

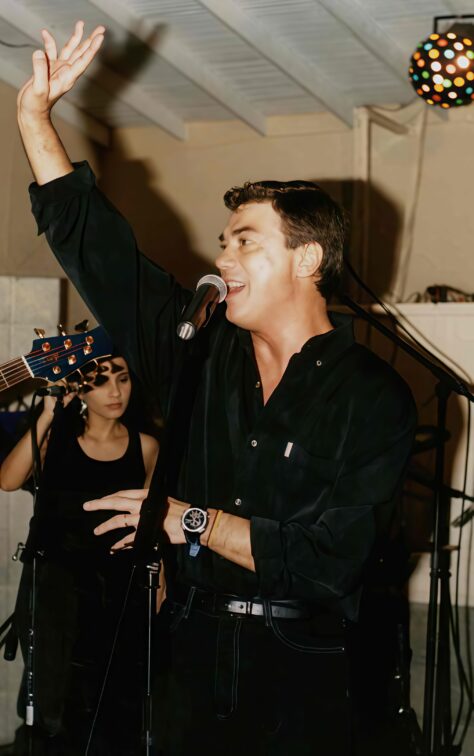

En 1999, ofreció lo que muchos consideran la actuación más emblemática de sus últimos años: un concierto de casi tres horas en el histórico Teatro Jorge Isaacs de Cali. Interpretó todos sus éxitos, desde ” Vuelvo a vivir”, “Vuelvo a cantar” hasta ” Pequeña y frágil “, entrelazando historias y recuerdos entre las canciones. Al final, empapado en sudor, susurró al micrófono: “Pensé que nunca volvería a hacer esto”.

A principios de la década del 2000, Sabú se volvió más selectivo con sus presentaciones. Sus conciertos se hicieron más pequeños e íntimos. Se centró en Colombia , donde el cariño del público nunca decayó. En 2004, ofreció uno de los conciertos más personales de su vida en Memorias Video Bar de Medellín , un lugar muy querido en el Distrito Cultural de la ciudad. El lugar estaba repleto de fans que lo habían seguido toda su vida.

El 7 de mayo de 2005, Sabú subió al escenario en Quito, Ecuador , para lo que, sin saberlo, sería su última actuación pública. Esa noche cantó, quizás sí, quizás no, con los ojos cerrados, agarrando el micrófono como si fuera un salvavidas. El público no lo sabía, pero presenciaba el fin de una era.

En julio, mientras se preparaba para actuar de nuevo en el Festival de las Flores de Medellín , empezó a quejarse de un dolor de cuello persistente. Pensando que se trataba de un nervio pinchado, los médicos programaron una cirugía de columna cervical. La operación salió bien, pero unos días después, algo cambió. Empezó a perder peso y a tener dificultad para respirar. Su energía se desvanecía. El 22 de julio, mientras continuaban los preparativos para su concierto en Colombia, Sabú se desplomó repentinamente. Su esposa, Josefina Gil, llamó al organizador del evento, quien también fue su último representante artístico, Fabián Montoya . Durante la llamada, le temblaba la voz. Pero Montoya logró oír la débil voz de Sabú de fondo diciendo: «No te preocupes, Fabián. Te veo allí. Quiero ir a Medellín». Fue la última vez que hablarían. Poco después, los médicos dieron la noticia que nadie quería oír.

Sabú tenía un cáncer de pulmón avanzado. Agresivo e inoperable. Solo le quedaba intentar un tratamiento paliativo con quimioterapia. En dos meses, soportó dos agotadoras rondas de tratamiento. La enfermedad progresó rápidamente, robándole la voz, la fuerza y, finalmente, el aliento. El 14 de octubre de 2005, Sabú fue trasladado de urgencia al Hospital Español de Ciudad de México. Apenas podía hablar. Josefina contaría más tarde que, al ingresar, llevaba una camiseta blanca de algodón, un regalo de sus fans en Medellín , con la inscripción «Sabú, Colombia te quiere. Vuelve pronto».

Nunca regresó. El domingo 16 de octubre de 2005, a las 10:30 a. m. en punto, Héctor Jorge Ruiz, aquel niño de Montserrat que dormía en parques, cantaba en seis idiomas y conquistaba corazones de todo el continente, murió en los brazos de Josefina. Tenía solo 54 años.

Videos

Soundcloud

Photos

Social profiles

Booking contacts

Agency: Memorias Producciones

Phone: +1 954 668 7735

Website: http://sabuoficial.com

Email: book@memoriasproducciones.com

Request availability

-

Buy my music on keyboard_arrow_down